Google Earth Studio is a web-based animation tool for Google Earth’s satellite and 3D imagery. It was first released in 2018 as an invite-only beta.

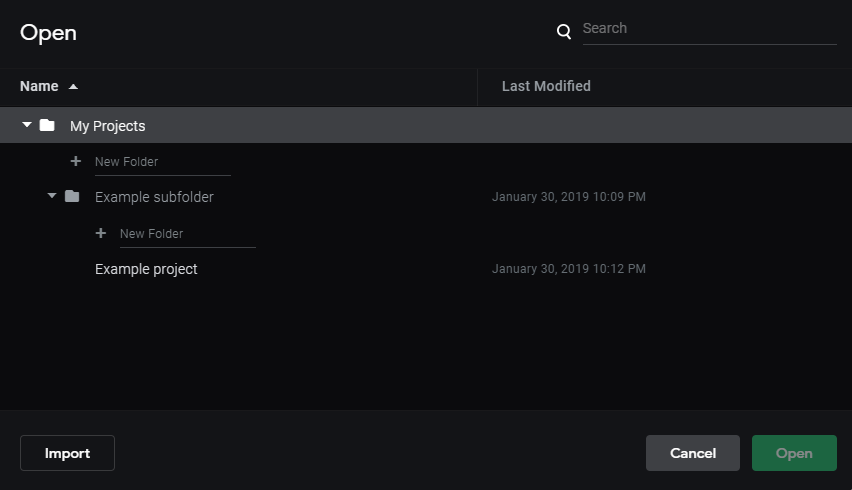

Creating projects and folders

Google Earth Studio lets users create 3D animations which are saved in projects. Each project contains information like its name, what folder it is stored in, when it was last created/edited, and so on.

Every project is saved in a folder — either the root folder or a sub-folder the user has created. Surprisingly, folders have incremental IDs. That means the first folder ever created has ID 0, the thousandth folder has ID 999 etc.

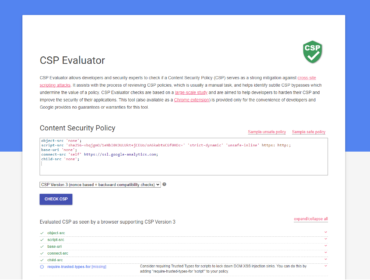

Allowing access to resources using incremental IDs (also known as IDOR = Insecure Direct Object Reference) is a bad practice as — if proper authorization restrictions are missing — it makes it possible to enumerate through all the entries that exist in the database. One way of preventing this is to use UUIDs.

Saving projects

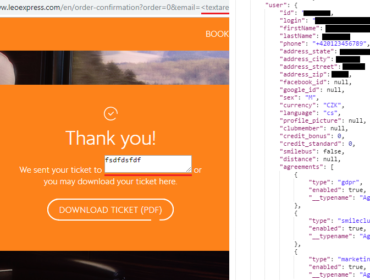

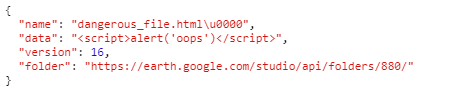

When a project is saved, a POST request is sent to https://earth.google.com/studio/api/projects/ with the following JSON body:

{

"name": "My project",

"data": { .... some json project data .... },

"version": 16,

"folder": "https://earth.google.com/studio/api/folders/31337/"

}The folder parameter contains a reference to the folder ID where it’s going to be saved, name is the title of the project and data contains a JSON object with the project configuration.

In this case, 31337 is an ID of a folder we have created before in our account. If however, another user creates a new folder in their own account that will have ID let’s say 12345 — and we use this ID (12345) instead of the ID of our own folder, the project will get saved there!

That means it’s possible to save our projects into folders that we don’t own.

Although the project is saved in the folder of another user, the user won’t see that project listed there. The code that shows the projects most likely checks if the user is the owner of the project as well.

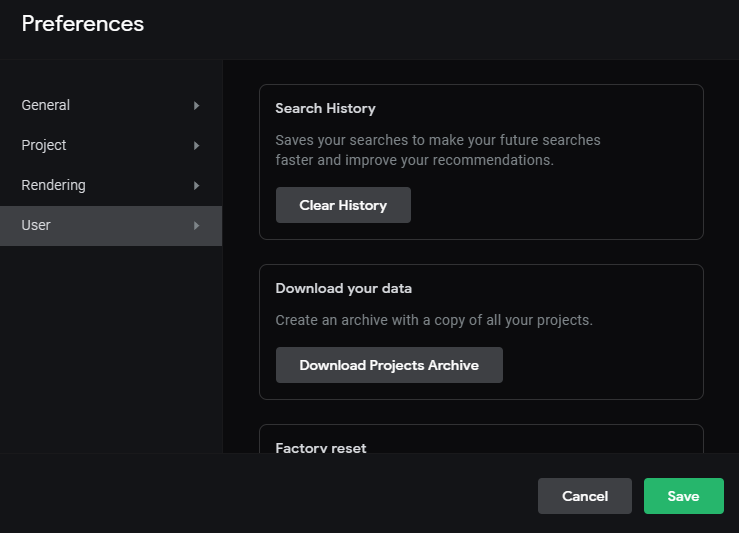

Projects Archive

There’s however a place where the project does show up in the folder — the Projects Archive.

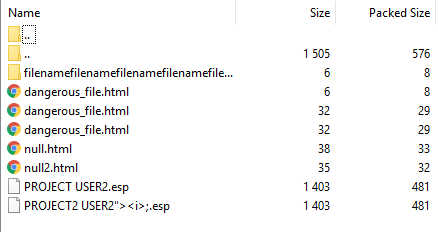

The Projects Archive is a zip file that contains a copy of all your projects.

The projects are stored in .esp files with their name as the filename and in corresponding folders. The content of the file is simply the data value as a serialized JSON. And this time the project we have created is included here as well.

So far we have found a way to save projects into zip archives of other users.

File payload

Since we know that the project’s data JSON value is reflected in the file’s content, we can try changing the JSON itself. As it turns out, we can change the value to any valid JSON. And a string is a valid JSON as well.

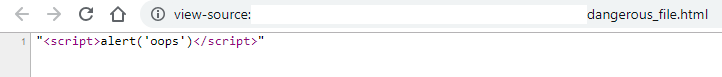

This means if we change the data value to <script>alert('oops')</script>, this payload is going to be reflected in the file as well.

So we have a file with a JavaScript payload saved in someone’s folder.

Changing the filename

When we open the file, the payload won’t be executed because the filename still ends with .esp. The filename is made with the project’s name and the just mentioned file extension. This gives us control of the filename — or at least the part before the extension — by changing the project’s name.

Changing the name simply to dangerous_file.html won’t work as the resulting filename will be dangerous_file.html.esp.

I tried to make the filename really long, hoping for some kind of overflow vulnerability that would make the filename end with .html. I’ve seen this one work in PHP, but unfortunately, it didn’t work this time.

Another option would be to add a null character at the end of the filename. Fortunately, adding special characters is easy in JSON. All we need to do is: dangerous_file.html\u0000.

In most low-level programming languages, a null byte represents the termination of a string, which means that what would be dangerous_file.html<NULL>.esp becomes dangerous_file.html just thanks to the fact that null is treated as the end of the string. Many frameworks/languages defend against this Null Byte Injection by simply not allowing null characters in the filename, but this was not the case at Google’s side.

Now we have a file saved in someone else’s folder, the file contains a JavaScript payload in a script tag, and the file is saved as .html.

Summary

Thanks to multiple combined vulnerabilities we are able to insert arbitrary files into anyone’s Google Earth Studio Projects Archive.

All we need now is that a user downloads their Projects Archive and opens the malicious file.

Google decided that this issue is not severe enough to qualify for a reward, but they fixed the vulnerability anyways.

Update from 2021

After two and half years after reporting the issue, I asked the team to reconsider this issue. I stated the following reasons.

My reasons:

- the attacker could insert almost arbitrary (must be valid JSON) files with a completely custom filename and extension

- the attacker could modify the archive of every project ever created on the service (due to incremental IDs), therefore affecting all users

Consider an example:

- the attacker inserts a valid executable file into everyone’s archive

- a victim downloads their archive from the Preferences page, extracts the archive, knowing it contains a copy of their projects downloaded from https://earth.google.com

The archive has a structure like this:

GoogleEarthStudio_MyProjects_07_28_2021/

└── Example Project/

├── projectData.esp

└── initProject.sh- the unsuspecting victim runs the

initProject.shfile, thinking it is a file that will “initialize” the project

The content of the file is: "$(custom code here)", which is valid JSON. In my case, for example, double-clicking the file on Windows with Git Bash installed directly runs the file. This is just one example of how the attack could be executed. I believe it’d be possible to create different executable files, however, I’m not really familiar with that and I think this is sufficient as a proof of concept.

While getting the victim to execute the file might seem similar to typical social engineering attacks, normally the attacker would send the file to the victim via a delivery channel, however in this case the victim would directly download the “archive with a copy of all your projects” from a website they trust (earth.google.com), without the knowledge that the archive of their projects has been infected with malware by the attacker. And the attacker could apply this to all projects/users using the service, leaving the “Download Projects Archive” option infected with malicious files for the entire service.

After providing the additional information, the VRP panel decided to issue a reward for this report.

| Timeline | |

|---|---|

| 2019-01-30 | Vulnerability reported |

| 2019-01-31 | Priority changed to P2 |

| 2019-01-31 | Accepted |

| 2019-02-05 | No reward issued |

| 2021-07-28 | Added more info and asked to reconsider reward |

| 2021-08-03 | Reward issued |